Our research

The Endoplasmic-reticulum stress and its sensing mechanism in yeast cells

Introduction

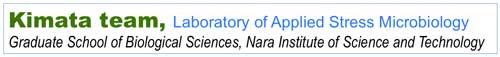

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a membrane-bound and flat- or tubular-shaped sac, which almost all of the eukaryotic (animal, plant and fungous) cells bears (Fig. 1). Ribosomes attach on the cytosolic side of the ER to form the rough ER. Newly synthesized peptides are thus co-translationally pushed into the sac and then transported out to the extracellular spaces or other organelles via the vesicular transport system. Transmembrane proteins are also co-translationally inserted into the ER membrane before being transported to cell surface or other organelles.

Fig. 1: The endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

(A) Electron micrograph of a goblet cell of mouse colon. Ribosomes (black dots) are attached on the ER membrane. (B) Fluorescent micrograph of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. The ER was illuminated by ER-localized GFP. Double-ring-like shape is observed, as the inner and outer rings are respectively the nuclear envelope, which is a kind of the ER, and the peripheral ER.

Dysfunction of the ER is collectively called ER stress, and in many cases, tightly related to accumulation of aberrant and misfolded client proteins in the ER. For example, overproduction or genetic mutation of an ER client protein causes its aggregation in the ER, triggers ER stress and then damages normal proliferation of cells. Eukaryotic cells generally evoke protective responses to overcome ER stress. The most well-known cellular response against ER stress, namely the unfolded protein response (UPR), is transcriptional induction of proteins working in the ER, such as the ER-located molecular chaperone BiP.

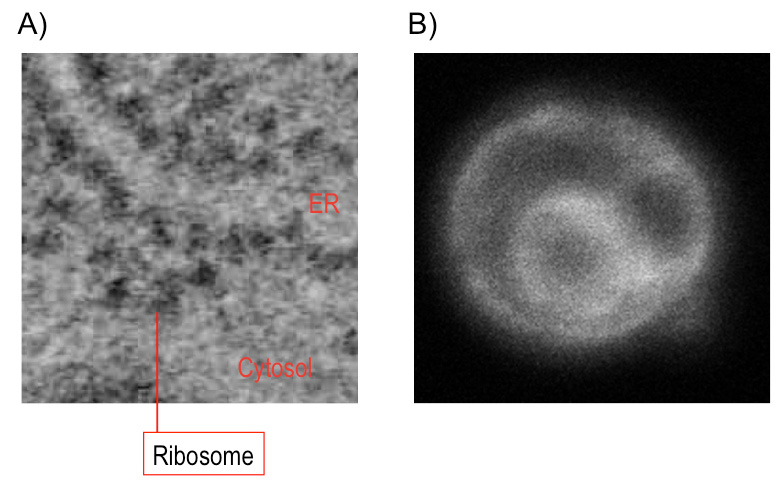

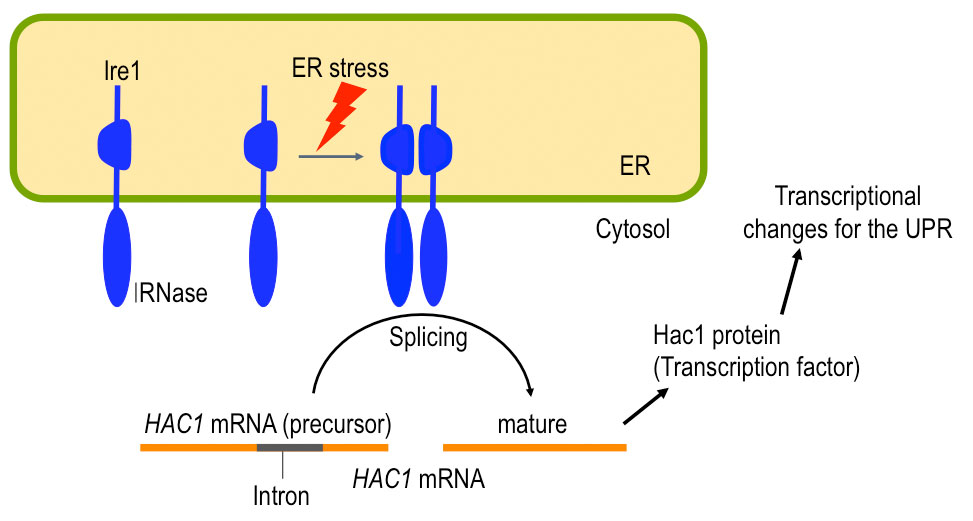

Ire1 is an ER-located transmembrane endoribonuclease conserved through eukaryotic species and serves as the UPR trigger. When budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells are exposed to ER stress, Ire1 is activated and promotes splicing of the HAC1 mRNA (Fig. 2). This reaction yields the mature form of the HAC1 mRNA, which is translated into a transcription-factor protein that is responsible for the transcriptional induction of the UPR. As shown in Fig. 3. we previously reported that Ire1 is highly self-oligomerized to form the Ire1 cluster in ER-stressed cells ( Kimata et al., 2007; Ishiwata-Kimata et al., 2013 ). It is highly likely that the clustered Ire1 molecules exhibit a potent RNA-cleavage activity.

Fig. 2: A role of yeast Ire1

Upon ER stress, Ire1 promotes splicing of the HAC1 mRNA, which results in transcriptional induction of the UPR target genes,

Fig. 3: Cluster formation of Ire1 in yeast cells

Yeast cells producing HA-epitope-tagged Ire1 were remained unstressed (No drug) or were ER-stressed with DTT before being subjected to anti-HA immunofluorescent staining.

Sensing ER stress by Ire1

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells have various stress-responsive systems to cope with various stressing stimuli, such as high or low temperature, oxidation, aberrant osmotic pressure, nutrient deprivation and chemicals. A cellular system is activated specifically in response to a stressing stimulus, while another cellular system works upon cellular exposure to another stressing stimuli. We thus believe that “the cellular system that a certain stress sensor is appropriately activated by a certain stressing stimulus” is an exciting research subject.

We have addressed this issue by employing the Ire1 and the UPR of yeast cells as a model system. According to our findings, Ire1 is regulated through multiple ways, which ensures tight regulation of the UPR. This is presumably because the UPR drastically changes the cellular transcriptome ( Kimata et al., 2005 ), and thus an inappropriate activation of the UPR impairs cellular proliferation.

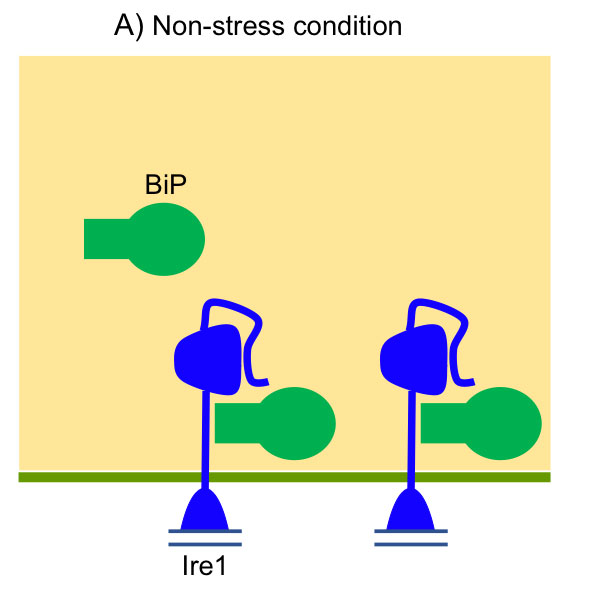

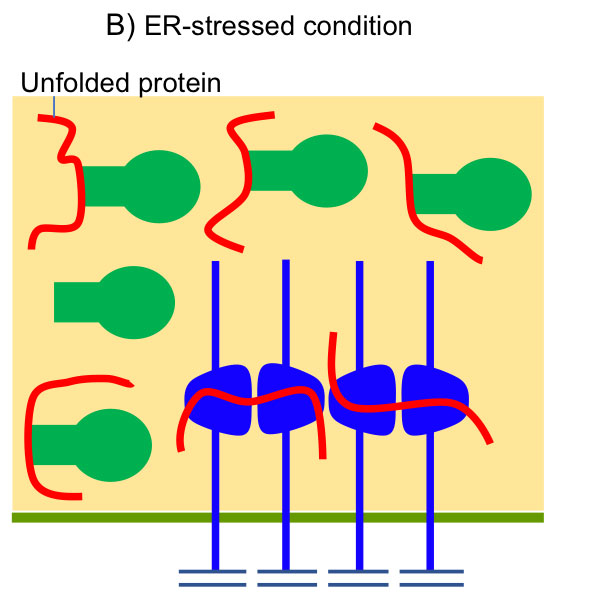

As shown in Fig. 4, BiP is associated with the luminal domain of Ire1 to suppress Ire1’s self-association and activation ( Okamura et al., 2000 ; Kimata et al., 2003 ). ER stress causes dissociation of BiP from Ire1, which, however, is not sufficient for activation of Ire1 ( Kimata et al, 2004 ). Unfolded proteins are directly captured by Ire1’s luminal domain for full induction of the UPR ( Kimata et al., 2007 ; Promlek et al., 2011 ). Moreover, the N-terminal loosely-folded segment of Ire1 inhibits activation of Ire1 under non-stressed conditions ( Mathuranyanon et al., 2015 ).

Fig. 4: Activation of Ire1 upon accumulation of unfolded proteins in the yeast ER lumen

(A) Under nonstress conditions, BiP is associated with Ire1 to inhibit its self-association. The N-terminal loosely folded segment of Ire1 also serves as a suppressor of Ire1’s activity. (B) Upon ER stress, BiP is dissociated from Ire1, which is then self-associated. The Ire1 dimers captures unfolded proteins acculumayed in the ER, and then clusters.

These observations well explain the molecular mechanism by which Ire1 is activated by unfolded luminal proteins accumulated in the ER. However, as well as wild-type Ire1, some of the Ire1 mutants which cannot capture unfolded proteins are activated by certain stressing stimuli ( Promlek et al., 2011 ). Since these stimuli are likely to commonly and strongly affect membrane status, we think that they are a distinct type of ER stress that is not tightly linked to unfolded luminal proteins. We are thus approaching molecular mechanism by which Ire1 is activated by membrane-lipid aberrancy or misfolding of membrane proteins.

Scenes in which the UPR is triggered in yeast cells

In order to evoke the UPR, yeast cells are genetically manipulated or exposed to chemicals which potently impair protein folding in the ER. Then, apart from these laboratory conditions, what kind of stimuli induces ER stress and activates Ire1 to initiate the UPR.

We previously found that ethanol is a potent ER stressor ( Miyagawa et al., 2014 ). Ire1 gene knock-out cells are super-susceptible to ethanol stress. These observations will be a foothold to find a contribution of the UPR system to yeast ethanol fermentation.

As for a matter concerning public health, cadmium, a toxic heavy metal, is known to initiate cellular responses against ER stress. In order to understand a toxic mechanism of cadmium, we have then addressed the molecular mechanism by which it activates Ire1 ( Le et al., 2016 ). Moreover, depletion of zinc, a trace essential metal, activates Ire1 and triggers the UPR ( Nguyen et al., 2013 ).

According to our previous reports, in these cases, the stressing stimuli is likely to impair protein folding in the ER, leading to the cellular responses against ER stress. On the other hand, we also found that the UPR is triggered upon diauxic sift of yeast culture through an unknown mechanism in which unfolded luminal proteins do not involved.