Functional Genomics and Medicine

Research

The NAISTrap Project

Welcome to NAISTrap!

Trends in Mouse Functional Genomics

With the animal genome sequencing projects approaching their completion, the next big task for our bioscience research communities is to rapidly and efficiently elucidate physiological functions in animals of the vast number of newly discovered genes and gene candidates.

Recently, an international collaborative project has been proposed to inactivate all mouse genes in ES cells within five years using a combination of random and targeted insertional mutagenesis techniques (1). To disrupt as many genes in ES cells as possible within a limited period of time, gene trapping will first be employed because it is simple, rapid, and cost-effective (2). Genes incapable of being captured by standard gene-trap techniques will then be subjected to labor-intensive and time-consuming gene-targeting experiments (1). Therefore, it is essential for the success of the project to establish an efficient gene-trap strategy suited to universally target genes in ES cells.

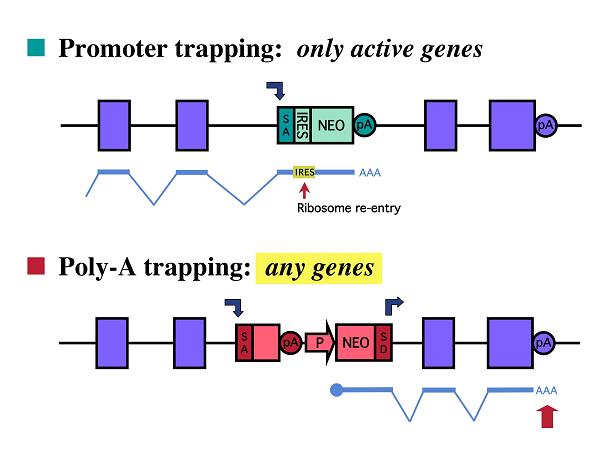

Two Ways of Gene Trapping

One of the most commonly used gene-trap methods is promoter trapping which involves a gene-trap vector containing a promoterless selectable-marker cassette (2). In promoter trapping, the mRNA of the selectable-marker gene can be transcribed only when the gene-trap vector is placed under the control of an active promoter of a trapped gene. Although promoter trapping is effective at inactivating genes, transcriptionally silent loci in the target cells can not be identified by this strategy. To capture a broader spectrum of genes including those not expressed in the target cells, poly-A-trap vectors have been developed in which a constitutive promoter drives the expression of a selectable-marker gene lacking a poly-A signal (2 & 4). In this strategy, the mRNA of the selectable-marker gene can be stabilized upon trapping of a poly-A signal of an endogenous gene regardless of its expression status in the target cells.

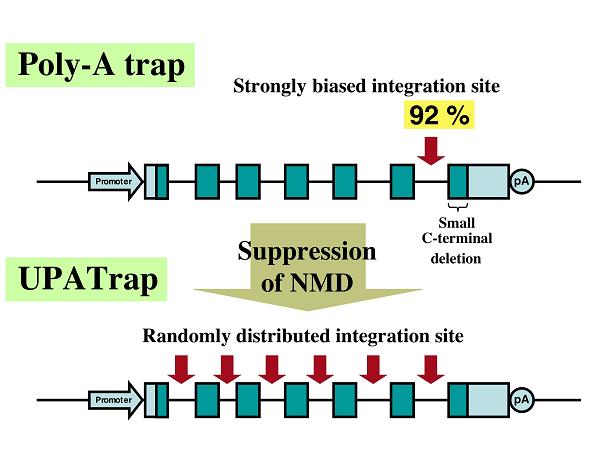

An Ideal Gene-Trap Method, UPATrap

Recently, we showed that despite the broader spectrum of its potential targets, poly-A trapping inevitably selects for the vector integration into the last introns of the trapped genes, resulting in the deletion of only a limited carboxyl-terminal portion of the protein encoded by the last exon of the trapped gene (8). We also presented evidence that this remarkable skewing is created by the degradation of a selectable-marker mRNA used for poly-A trapping via an mRNA-surveillance mechanism, nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD)(8). The NMD pathway is universally conserved among eukaryotes and responsible for the degradation of mRNAs with potentially harmful nonsense mutations (3).

We showed that an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) sequence (EMCV-derived) inserted downstream of the authentic termination codon (TC) of the selectable-marker mRNA prevents the molecule from undergoing NMD, and makes it possible to trap transcriptionally silent genes without a bias in the vector-integration site (8). We believe this novel anti-NMD technology, termed UPATrap, could be used as one of the most powerful and straightforward strategies for the unbiased inactivation of all mouse genes in the genome of ES cells (1).

Database for the NAISTrap ES-Cell Resource

Genes are randomly trapped using the RET (4) or UPATrap (8) vector in a mouse ES-cell line to create a large panel of gene-trapped ES clones.

In the NAISTrap database, the following features are described for each ES-cell clone:

- Clone number

- Name of the trapped gene

- Expression of the trapped gene in undifferentiated mouse ES cells (as inferred by the GFP fluorescence in each ES-cell clone)

- Identity between the trapped sequence and the one in the NCBI databases

- Size and location of a coding sequence (CDS) on the corresponding mRNA in the NCBI databases

- Region of the CDS deleted due to the gene trapping

- Nucleotide sequence of the trapped cDNA recovered as a 3' RACE fragment

The NAISTrap clones are made available to the general academic scientific community, free-of-charge! Please e-mail us at "naistrap@bs.naist.jp" and let us know in which clones you are interested.

How to Find the NAISTrap ES-Cell Clones of Your Interest

Unfortunately, thus far it is impossible for researchers ouside NAIST to perform the BLAST-type search against our database by using raw DNA sequences. However, if you are not uncomfortable to send us (at "naistrap@bs.naist.jp") such DNA sequences by e-mail, we are more than happy to examine, by using our in-house computers and software, if we have ES clones in which your genes of interest are trapped.

Alternatively, you can perform by yourself the BLAST search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) against a database of NCBI and may be able to find the NAISTrap ES-cell clones of your interest there because we started to submit our gene-trap sequences to NCBI in the summer of 2005. For this purpose, try the nucleotide-nucleotide blast (blast-n), and choose the gss database as the target. If you are lucky enough to find such clones, remember their ID numbers and come back to our NAISTrap database here. You should be able to find a lot more useful information about the clones in our website.

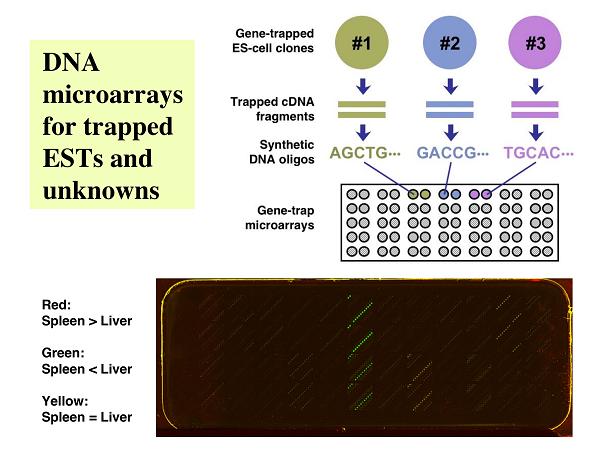

Gene-Trap Microarrays

DNA arrays are capable of profiling the expression patterns of many genes in a single experiment. After finding a gene of interest in a DNA array, however, labor-intensive gene targeting experiments sometimes must be performed for the in vivo analysis of the gene function. With random gene trapping, on the other hand, it is relatively easy to disrupt and retrieve hundreds of genes/gene candidates in mouse ES cells, but one could overlook potentially important gene-disruption events if only the nucleotide sequences and not the expression patterns of the trapped DNA segments are analyzed. In order to combine the benefits of the above two experimental systems, we constructed arrays of cDNA fragments (or synthetic oligos) derived from the disrupted genes (7). Using these arrays, we can identify a novel gene with an interesting expression pattern, and the corresponding ES-cell clone will be used to produce mice homozygous for the disrupted allele of the gene. Identification of a gene or a novel-gene candidate with an interesting expression pattern using this type of DNA arrays immediately allows for the production of knockout mice from an ES-cell clone with a disrupted allele of the sequence of interest.

References: Background

- Austin, C. P., Battey, J. F., Bradley, A., et al. (the Comprehensive Knockout Mouse Project Consortium). The Knockout Mouse Project. Nat. Genet. 36, 921-924 (2004).

- Stanford, W. L., Cohn, J. B. & Cordes, S. P. Gene-trap mutagenesis: past, present and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 756-768 (2001).

- Maquat, L. E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 89-99 (2004).

References: Our Publications

- Ishida, Y. & Leder, P. RET: a poly A-trap retrovirus vector for reversible disruption and expression monitoring of genes in living cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, e35 (1999).

- Goodwin, N. C., Ishida, Y., Hartford, S., Wnek, C., Bergstrom, R. A., Leder, P., and Schimenti, J. C. DelBank: a mouse ES-cell resource for generating deletions. Nat. Genet. 28, 310-311 (2001).

- Shimizu, J., Yamazaki, S., Takahashi, T., Ishida, Y., and Sakaguchi, S. Stimulation of CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 3, 135-142 (2002).

- Matsuda, E.*, Shigeoka, T.*, Iida, R., Yamanaka, S., Kawaichi, M., and Ishida, Y. (*equal contribution) Expression profiling with arrays of randomly disrupted genes in mouse embryonic stem cells leads to in vivo functional analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 4170-4174 (2004).

- Shigeoka, T., Kawaichi, M., and Ishida, Y. Suppression of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay permits unbiased gene trapping in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e20 (2005).

- Shimizu, J.*, Iida, R.*, Sato, Y., Moriizumi, E., Nishikawa, A., and Ishida, Y. (*equal contribution) Crosslinking of CD45 on suppressive/regulatory T cells leads to the abrogation of their suppressive activity in vitro. J. Immunol. 174, 4090-4097 (2005).

The NAISTrap Members

- N. Ika mayasari

- Bai Jie

- Tubasa Watanabe

- Yoh Furuya

- Aya Kimura

- Yuka Kimura

- Aya Ozaki

- Masashi Kawaichi, M.D., Ph.D.

- Yasumasa Ishida, M.D., Ph.D.